Home » Industry Watch

Quick: Elizabeth Day Travels to SwedenOne of the grossest miscarriages of justice in recent times?

SÄTER (Rixstep) — The story of Sture Bergwall aka Thomas Quick and the legal corruption surrounding what's been agreed is the grossest miscarriage of justice in the history of Sweden continues to unravel. Now Elizabeth Day took a trip to Sweden to tell the story to the world outside the Duckpond.

Elizabeth Day is an award-winning Observer journalist and novelist who took it upon herself to travel to Sweden, meet with 'hair on fire' attorney Thomas Olsson (he of the local Assange legal team) and pair with him on the trek to Säter hospital where Sture Bergwall, once known as Thomas Quick, is still incarcerated more than twenty years after donning a Father Christmas kit and robbing his own bank office in a sort of 'creative protest'.

Elizabeth Day's done her homework: In this, perhaps the first major international exposure of the judicial scandal that's rocked the Scandinavian country and been classed as the greatest such scandal in history, she gets not a single fact wrong, and manages to include the whole ball of wax, save for the identities of those who made it possible (and profited immeasurably by it).

Day's piece will bring new light on the reason there's so little confidence in a judicial system that only a few years ago did not gain widespread attention, despite legal experts crying continually for much-needed reform.

For how can one convict a drugged-out pathological liar of eight murders when no evidence is available? What happened to presumption of innocence and 'guilty beyond a reasonable doubt'? The answer is buried in the 50,000 pages of court and police documents, and the answer is unequivocal: the police and prosecutors hid vital facts from the courts who in turn had no inkling things were being hidden, no way to know what was really going on.

The police investigations, by accepted standards, were haphazard, sloppy, and foolishly naive. The prosecutor, a lacklustre sort who up to then was most known for not having obtained a single conviction, became obsessed with pinning murders his people had been unable to solve on a guest at one of the country's mental institutions. And the defence attorney, called into replace the original defender who quit in protest over the unethical methods being used by the police and prosecutor, calmly decided to keep his mouth shut so as to not jeopardise his reward of over US$500,000 for not just essentially but specifically doing nothing at all.

A win-win situation for all those involved. Save for Thomas Quick himself of course. And save for the families and friends of the victims who understood all along that the Quick investigations were a sham.

The Swedish media can be blamed as well. Anyone following the Assange case has long since understood that the Swedish media can rightfully be blamed for most anything.

Arrival

Day begins her narrative with her arrival at Säter, painting a Flemingesque picture.

A high wire fence circles the building. CCTV cameras track the movements of the outside world. The narrow windows - some of them barred - are smudged with dirt and thick with double-glazed glass. In order to visit, you must enter through a succession of automatically locking doors and walk through an airport-style security gate. You must leave your mobile phone in a specially provided locker and hand over your passport in return for an ID tag and a panic alarm. Two members of staff, wearing plastic clogs that squeak across the linoleum, escort you through the corridors.

She meets Quick - today using his real name Bergwall - in a visitors room where Bergwall is sitting attentively. Bergwall, now 62 years old, occasionally puts snus under his upper lip. Day's overall impression is of 'a kindly, slightly shy, older man who is eager to please'. Despite his incarceration, things have been looking up for him: he receives his extended family from time to time, and today he has his own blog and a Twitter account where he is very active.

'What will you do if you ever get out of here?' Day asks him.

'I'll just walk straight ahead and keep going.'

Bergwall - then taking the name Thomas Quick on the suggestion of psychotherapist Birgitta Ståhle who thought Bergwall might want to protect his family - confessed to some thirty murders over the years, many of which could not possibly have occurred as the alleged victims were alive - something prosecutor van der Kwast and defence attorney Borgström were fully aware of. He was also given permission to travel without chaperone to the capital where he'd visit the royal library in Humlegården to cull new facts from unsolved murders he could later claim he'd committed himself.

When confronted with this obvious blunder, prosecutor Christer van der Kwast felled an immortal response to investigative reporter Hannes Råstam, tantamount to 'so what, I don't see the connection'.

Bergwall aka Quick was heavily drugged at the time. No hospital in Sweden would dare administer drugs in those quantities anymore. He was also victimised by an ambitious psychotherapist who sensed she was on the cusp of a major breakthrough in regression therapy and the recovery of 'lost memory'. It would take Hannes Råstam a trip to Harvard University in the US to find out just how ridiculous the whole thing was.

Säter had a changing of the guard in management in 2001. The new people in charge reviewed the situation and quickly came down on the abuse of narcotics - Quick had been given unlimited access to most anything he wanted. No longer higher than the Empire State Building, Quick quickly tired of making up tall tales, took what he called a 'time out' in his work with the authorities, reverted to use of his real name, and became - lo and behold - rather normal, sane, and pleasant.

Yet management at Säter haven't been happy with the growing scandal, as one by one the old convictions are being overturned by the courts. Several people, including Bergwall himself, have accused the hospital of enacting revenge on Bergwall in a number of ways, perhaps because his continuing story embarrasses them.

Hannes Råstam

Hannes Råstam (RIP) is Sweden's foremost investigative reporter ever. Originally a bassist with one of Sweden's well known rock acts, he jumped ship and enrolled in journalism school and went on to uncover some of the most frightening travesties of justice imaginable in sweet little innocent Sweden. Travesties such as the case of 'Ulf' where a deputy prosecutor-general was knowingly and willfully withholding crucial information from the court system so a completely innocent man ended up spending three years behind bars with about as much a clue of what was going on as an antihero in a novel by Franz Kafka.

Råstam was instrumental in not only rescuing victims from Sweden's grotesque justice system, but in making people everywhere understand just how vulnerable that justice system is.

A Lonely Place

Performance artist Bergwall - who did have a criminal record - was taken out of his Father Christmas kit and placed in an institution with hardened dangerous criminals. 'I noticed that the worse or more violent or serious the crime, the more interest someone got from the psychiatric staff.' So when Birgitta Ståhle decided that bank robberies in Father Christmas suits must be caused by traumatic childhoods and decided to 'un-repress' Bergwall's memory, he complied. The stories he made up got more colourful as Ståhle and others pumped him full of more and more drugs, Xanax being one of the most popular.

No one before Hannes Råstam had seen the medical journals which itemise just how much Xanax they were pumping into Bergwall each day.

Perhaps one of Bergwall's most colourful stories ever was the one about how he was raped by his father in the same room his younger brother Simon was being born, only to accompany his father into the woods after the birth to chop the newborn into tiny pieces and bury them. Ståhle was so excited by this story that she contacted the police, and things went from there.

Police inspector Seppo Penttinen took over - and according to acknowledged experts Råstam met with in the US, committed about every possible blunder imaginable. Penttinen talked way too much in the interrogations. He unwittingly gave details to Bergwall that he was later surprised Bergwall could know about. He was caught on film describing a murder weapon Bergwall repeatedly failed to describe, only to report confidently to the prosecutor that Bergwall had succeeded in identifying it.

The courts never saw the misfired confessions and police blunders. They never saw the police protocols which made it embarrassingly obvious that the entire case was ridiculous nonsense. All they saw was that someone had calmly and mostly without error confessed to a series of crimes. That Bergwall's testimony could not be backed up by a single piece of hard forensic evidence was something Swedish courts traditionally don't worry too much about: an untold number of innocent men are behind bars right now because former spouses and girlfriends make up stories for one reason or another - got caught by another lover, bogged down in a custody battle, out for a pecuniary reward, to name but a few motives admitted by the women over the years.

Perhaps the most tragicomical of these is the da Costa case, where a woman was in a court battle with a former spouse and decided to coach their three year old daughter to tell a bizarre tale she was to claim she remembered vividly when she was but one and a half. And the courts swallowed it hook line and sinker.

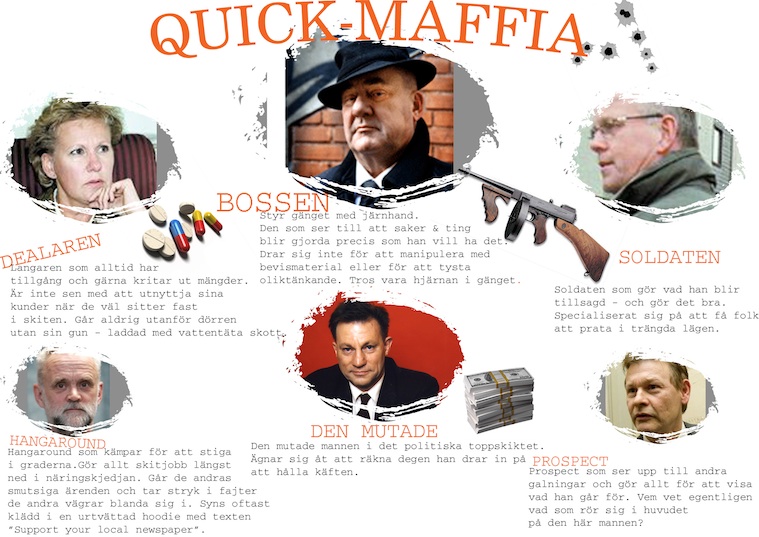

The Quick Mafia

There are many people to blame in the Quick scandal. Collectively they're known as the 'Quick mafia' as they all profited handsomely by the affair. But at the head of it is prosecutor Edward Christer Van Der Kwast, today retired, who time and again discarded hard evidence which disproved his case, who made sure Quick's defence attorney remained cooperative, and kept the full truth hidden from the courts.

And that defence attorney was none other than the notorious Claes Borgström, most known today for reopening the rape case against Julian Assange and for methodically smearing Assange in the Swedish media, to the point there's tangible Assange-hate rampant in the country.

Borgström also experienced a growing disgust amongst his fellow Swedes with his behaviour in the Quick cases - he was, after all, a defence attorney, and fully capable of stopping van der Kwast, if only he'd wanted to. After miles of newspaper columns and dozens of books were written about Quick - all implicating Borgström up to and beyond his bloodshot eyeballs - he pulled a 'fast one' right at the time of the Collateral Murder video: he wrote an open plea to the Swedish bar association to fully investigate his part in the Quick scandal, and to disbar him if necessary: a 'fast one' in that only Borgström and assorted legal experts knew the bar association could not legally act on such a published plea.

Anna Ardin

Anna Ardin sought out Claes Borgström on the weekend of 20 August 2010, after she got too implicated in what was supposed to be a complaint related only to Sofia Wilén, and saw how chief prosecutor Eva Finné closed the Wilén case already the following afternoon.

That she beseeched Borgström to reopen the rape case is out of the question: Borgström admitted in a filmed interview that Ardin hadn't even known such a thing was possible, despite her years as police liaison at her university. But by then Ardin had found herself inadvertently dragged into the affair, and her part of the case was not classified as a 'crime against the state', so she was legally culpable for testimony in a way Sofia Wilén would never be.

And then Ardin further complicated matters by suggesting she still had the condom she and Assange had used over a week earlier, and by supplying the police who came right around to fetch it with an unused such, conveniently torn in much the way she'd described in her phone interview with the police inspector that same day.

But the condom of course had no chromosomal DNA whatsoever, proving she'd fabricated the evidence, a felony under the circumstances.

So Claes Gustaf Borgström was back in business again.

'He Got Zero Right'

Perhaps the most embarrassing case of them all: the case of Therese Johannessen, a nine year old girl in Norway. Quick was asked to describe the crime and the victim. The crime took place in the countryside where Therese lived, said Quick. Therese was a little blonde girl with blue eyes, dressed in a jump suit, and had prominent buck teeth. And the weather? Gloriously sunny, said the gambler Quick.

But Therese lived in a high-rise, was part Pakistani, had dark hair, had no front teeth, was wearing only a light t-shirt and jeans - and the day of the crime was the worst downpour in Norway in ten years.

Despite all this, van der Kwast decided to continue, Borgström said not a word, and then Quick came with the most unbelievable story of all time. After hearing what details of his story were inaccurate, he explained that his repressed memories first appeared as film negatives - so the details he shared with inspector Penttinen were of course the exact opposite of the truth.

Quick also introduced the concept of 'planned errors', something Ståhle bought immediately. And the story of why he got every detail diametrically wrong in describing the murder of little Therese? They all bought that too. And Borgström never said a word.

Borgström has at time attempted to excuse his lack of intervention with the argument that his client indicated he wanted to be convicted. This is a lame excuse and shows a deep contempt for the law and the judicial system.

Back to Stockholm

Elizabeth Day rode back to Stockholm with Thomas Olsson, one of two lawyers Julian Assange has hired. Olsson and the other lawyer, Per E Samuelson, are considered the best attorneys in the land. Samuelson totally demolished John Kennedy of the IFPI in the trial of The Pirate Bay and has published a textbook on cross-examination techniques.

Olsson, from the law firm of Leif Silbersky, otherwise Sweden's most famous attorney and Assange's original counsel, was Sweden's most prominent defence attorney in the myriad crazy rape cases that spread like an epidemic throughout the land, but finally said he'd had enough - they were simply too taxing, despite his stellar record. That he's back again can only be seen as a good sign, and that he represents Thomas Quick can't be but good. Five out of the eight convictions have already been tossed out, and the remaining three are bound to go the same way.

'A lot of people made their careers on Thomas Quick', says Olsson's assistant Jenny Küttim. 'So today they have a lot to lose.'

Thomas Olsson of course expects the final three verdicts to be overturned as well, after which he'll begin the fight to get Bergwall's release from Säter. Olsson tells Day that the Quick case 'raises serious questions about the entire legal system'.

Elizabeth Day has done a remarkable thing in bringing the Quick case into the international arena. Eight murder convictions all reviewed and approved by a happy-go-lucky Göran Lambertz in a single week back in 2006 when he was chancellor for justice, and not a one of them stands.

Assange & Quick

There is every reason to compare the Quick scandal with the ongoing Assange scandal. Assange and Quick are not the only people who've come to harm's way in the Swedish Duckpond. And many of the types of dramatis personae in both cases are familiar (and in one case identical). The Swedish media in both cases did their utmost to stoke the judicial system against the accused. And both cases serve to shine a light on endemic flaws in Swedish jurisprudence.

Presumption of innocence, unbiased police investigations, dismissal of circumstantial evidence, absolute requirement of hard forensic evidence - these and other concepts remain alien in the Duckpond where convictions can still be based on a 'hunch' or 'gut feeling', and where police and prosecutors are in the habit of withholding the truth.

Until the Swedish judicial system is subjected to a comprehensive audit and overhaul, no one in the country goes safe.

See Also

TV4: Jan Guillou and Göran Lambertz (Swedish)

Elizabeth Day: Observer: Thomas Quick: the Swedish serial killer who never was

Salomonsson Agency: Fallet Thomas Quick/The Making of a Serial Killer by Hannes Råstam

Industry Watch: Quick #4

Industry Watch: Assange's Dream Team

Industry Watch: Third Quick Case Dismissed

The Technological: So Proud, So Proud

Flashback: The Monster WikiLeaks Thread

Red Hat Diaries: Assange: Fair Trial in Sweden?

Marcello Ferrada de Noli: Why Blame Julian Assange?

Red Hat Diaries: The Claes Borgström Interview

The Technological: How to Earn a Cool Half Million

Red Hat Diaries: Quick: My Final Chat with Borgström

Red Hat Diaries: Sweden's justice system stands accused

Red Hat Diaries: Sweden & The Rule of Law

Red Hat Diaries: Justice in Sweden: The Ulf Files

Industry Watch: 709 Swedish Jurists Agree with Assange

Learning Curve: No Requirement of Proof in Swedish Sex Trials

Industry Watch: Twelve Hours That Shook the World

|