Home » Learning Curve

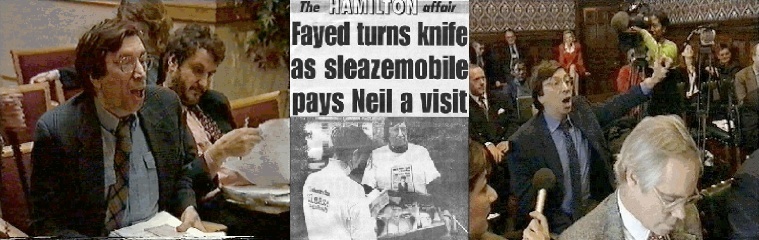

Who wouldn't shout with the stakes so highThe real story of Heather Brooke, David Leigh, Ian Katz, and Alan Rusbridger.

Note: the following is an excerpt from Canongate's copy of the autobiography of Julian Assange which was never completed and never approved for publication. It is interesting and informative in that it tells the real story of Heather Brooke, David Leigh, Ian Katz, and Alan Rusbridger. They're not mentioned by name in the book - that'd be beneath Julian Assange - but everyone familiar with the saga will recognise them.

Amongst other things we learn that:

√ Julian Assange saw 'trouble ahead' and began securing backups of Cablegate with resources across the globe. He secured copies in eastern Europe - the copy later widespread came from Croatia - and in Cambodia where Gottfrid Svartholm Varg (aka Anakata, cofounder of The Pirate Bay and collaborator on the Collateral Murder project) was thought to be ensconced.

√ Icelander and former WikiLeaks volunteer Smári McCarthy was also entrusted with a copy of Cablegate - and he in turn chose to turn over a copy to Heather Brooke - a decision right up there with the hiring of Daniel Domscheit-Berg. Brooke, a native of the US living in the UK, had gained notoriety for her involvement in exposing the UK parliamentary expenses scandal. Upon acquiring a copy of Cablegate from the Icelander, Brooke regarded her booty with glee and thought to herself 'oh now who can I sell this to?'

√ She ended up 'selling' Cablegate to the Guardian's David Leigh who had already been given a copy by Julian Assange after editor Alan Rusbridger had signed the all-important 'memorandum of understanding', binding the Guardian to a number of conditions none of the editors ever respected. Leigh saw the advantage of having another copy of Cablegate, as that would protect his brother in law's Guardian from legal repurcussions if they went behind Assange's back, collaborated with the New York Times, and released Cablegate without Assange's knowledge. David Leigh actually gave the cables to the Times long before Heather Brooke entered in the picture. 'I think I uploaded the stuff to a secure NYT server', he wrote. But it was Brooke's copy that gave him his 'alibi': she essentially became the legal fiction that gave the Guardian the excuse to break the agreement.

√ David Leigh, Alan Rusbridger, and Ian Katz secretly plotted to release Cablegate on 8 November without Julian Assange's knowledge, using the Heather Brooke copy as their 'legal out'. Someone connected to the plot evidently didn't approve, as the word got out.

√ Assange found out about the betrayal and brought Mark Stephens with him to the Guardian's offices to sort matters out.

√ The only way Assange could stop Leigh and the Guardian from their planned release was to threaten to give the entire Cablegate to Rupert Murdoch's News Corporation. This finally frightened Guardian editor Alan Rusbridger into overruling his brother in law and again dealing with his 'whistleblower source'.

√ Assange encountered Leigh on the night in question standing beneath a stairway in the Guardian's offices. Leigh hadn't known he'd been found out and according to Assange turned 'white'. 'I've never seen anyone's face collapse like that', Assange recounts.

And now the story - as found in the 'unauthorised autobiography'.

Disclosure is not merely an action; it is a way of life.

To my mind it carries sense and sensibility: you are what you know, and no state has the right to make you less. Many modern states forget they were founded on the principles of the Enlightenment, that knowledge is a guarantor of liberty, and that no state has the right to dispense justice as if it were merely a favour of power. Justice, rightly upheld, is a check on power, and we can only look after the people by making sure that politics never controls information absolutely.

This is common sense. It used to be the first principle of journalism in every country with a free press. Early in our relationship with the media partners, I knew I would, at some point, offer them the chance to join us in publishing a giant cache of diplomatic cables. I was holding off, to let the Afghan and Iraq war logs see the light of day in as measured and careful a way as possible.

As a result of surveillance and the aggressive attitude of the Pentagon towards me, I wanted to make copies of the cables to ensure their safekeeping. I was not happy with how things had developed with the Guardian, but my attitude was 'better the devil you know'. The New York Times had shown themselves to be cowards, and I was not ready to work with them again. It felt like there was a massive strike coming down on us, so I copied the 250,000 documents and stashed them first with contacts in Eastern Europe and Cambodia. I also put them on an encrypted laptop and had it delivered to Daniel Ellsberg, the hero of the Pentagon Papers. Giving it to Dan had symbolic value for us. We also knew he could be trusted to publish the whole lot during a crisis.

'There were some incredible stories in the cables.'

I asked for a signed letter from the Guardian's editor, Alan Rusbridger, guaranteeing the material would be kept confidential, that nothing would be published until we were ready to go, and that it would not be stored on a computer that was connected to the internet or any internal network. Rusbridger agreed and we signed the letter. In return, I produced an encrypted disk with a password and they had the material. At which point the senior news reporter went off on holiday to Scotland, all bonhomie and jollity, ready to read the material and keep in touch about the future plan.

With the Swedish case now in the air, there was a definite sense of gossiping schoolgirls among the media partners.

It amazed me, because many of them are investigative reporters, and you'd imagine they knew something about smears and hysteria when it came to political outcasts. A man, for example, who worked for the Bureau of Investigative Journalism suddenly told his colleagues he wouldn't 'appear on stage with a rapist'. Some of those men have more skeletons in their closets than Highgate Cemetery but they dived on my troubles with an unmistakeable glee.

None asked me how it came about, or how I was, or whether I needed anything: they simply responded as if the creepy allegations were 'smoke' that could not possibly exist 'without fire'.

Having schmoozed their way to several scoops off the back of our organisation, two of these media partners began to behave as if I represented a moral risk. Nothing had changed in the material, nothing had changed in our passion to reveal it, but false allegations had been made against me that caused these men to increase their bad behaviour and their stereotyping of me to the point where it was crazy.

There were some incredible stories in the cables: $25 million worth of bribes to politicians in India, given with the knowledge of apparently sanguine US diplomats; signs of continued American interference in Haitian politics; revelations that a Peruvian presidential candidate had taken money from an alleged drug trafficker; unprecedented levels of lobbying of foreign governments by diplomats on behalf of American corporations; politicians in Lithuania paying journalists for positive coverage; and even spying by American diplomats on their colleagues at the United Nations.

'The Guardian reporter's argument is she was shopping them around.'

The cables were going to be sensational, but at that point they were not quite ready. Any decent publisher would have understood this: it was more important than any scoop that the material be properly ready and the sources be protected. This was priority number one. But not to the Guardian. No sooner had the senior reporter returned from his holiday than he began harassing me about publication. He said a rival journalist had a copy of the cables and was a clear threat to their exclusivity.

I investigated that matter. It turned out that our Icelandic colleague Smári McCarthy had indeed shared the material with the journalist during an anxious moment.

Stressed at his workload, McCarthy had misguidedly shared them with her - to get some help - under certain strict conditions. He then hacked into the computer remotely and wiped the cables, though it would never be clear whether she had copied them or not. The Guardian reporter's argument is that she was shopping them around.

I can't tell you how many times we have come across people - people who think of themselves as campaigners - behaving like stock exchange bullies when it comes to a commodity they are interested in. You can hear the snap of their red braces as they go in for the kill.

The Guardian's senior reporter said it was all very threatening and he wanted to rush towards publication. I told him we weren't ready and we had a written agreement. He went off in a fluster and we didn't hear from him.

It became clear later that he had already copied the material for the New York Times. They were moving towards publication with no regard for any of the important issues - matters of life and death - that stood behind the documents. Like greedy, reckless, damn-them-all bandits, they were going to shoot up the town no matter who was standing in the way. The Guardian's reporter had behaved cravenly and lawlessly, and was quite happy to please his newspaper, and his heroes across the Atlantic, while dumping the whole thing on our heads without warning... WikiLeaks could go and hang itself from the nearest tree.

'I've never seen anyone's face collapse like that.'

We simply had to have some time. It was deeper than any of them could understand, in their juvenile deadline-mania, but we had to have time to prepare for this. I called Rusbridger and he agreed I should come in for talks. I knew they were double-crossing us, without even having the balls to say that was what they were doing. We came into the building with my lawyer, Mark Stephens, and came face to face with the senior news reporter beside the stairs.

'Hello', I said.

'Oh-oh', he said, surprised.

'We'll come down and see you later', I said. 'We just want to clarify a few things that Alan Rusbridger showed us.'

I've never seen anyone's face collapse like that. He went white. As we walked away, our group said the news reporter looked like a person caught with a murder weapon.

We went upstairs to see Rusbridger. Der Spiegel's editor came in. I was shouting, almost certainly, and I asked Rusbridger point-blank if they had given the material to the New York Times. He dodged the question.

'The first thing we need to do', I said, 'is establish who's got a copy of the material. Who does not have a copy of the material, and who does? Because we're not ready to publish.'

His eyes rolled around the room. He didn't know where to look.

'Did you give a copy of the cables to the New York Times?'

I kept pressing them. 'We need to understand what sort of people we're dealing with. Are we dealing with people whose word we can trust or are we not? Because if we're not dealing with people whose written word we can trust, then...'

It now looked like all their eyes were rolling round the room. It was like a cartoon, all these grown men finding themselves unable to face the truth of what they had done, or to put forward some argument to try to defend themselves. I would later be characterised as some sort of nutcase for shouting at them. But who wouldn't shout, when the stakes were so high? Who wouldn't lose their temper with such lily-livered gits hiding in their glass offices? It was soon clear to everyone that Alan's refusal to answer the question was as good as an admission. It was only for legal reasons that he wasn't saying 'yes' or 'no'.

My respect for the man plummeted... here's this guy, the editor of an important newspaper, an institution, a man older than me and with a crucial issue in front of him, and what we get is eyes rolling around the room like marbles on a pogo stick. I couldn't believe I was witnessing it.

We ended up debating it for seven hours, then we went downstairs to come up with a plan.

The Guardian had known all along what it wanted to do - it wanted to publish right away. Der Spiegel was trying to be friends with everyone. The truth is, we weren't ready to go, and we were being strong-armed by these people who had been niggling away at us for weeks, and were now ready with the coup de grace. At the centre of their colossal, stained vanity, they had forgotten who we were and how we had got to this room. They now thought of us as a bunch of weird hackers and sexual delinquents.

But we knew our material and we knew our technology; these guys were playing by the oldest rules in the business.

'The Guardian had been ready to fuck us all along.'

I implied that I would immediately give the entire cache of material to the Associated Press, Al Jazeera and News Corp. I didn't want to do it, but I would if they didn't play ball.

They sobered up and began to speak more reasonably about how the publication might be handled.

It later emerged, via the guys at Der Spiegel, that the Guardian had been ready to fuck us all along. They were working with the New York Times and were willing to go without even telling us, and without giving us a chance to prepare the data properly or prepare ourselves for attack.

That's how much the Guardian actually cared for the principles involved. Openness? You must be joking. A new generation of libertarians? They couldn't have cared less.

A new mood of popular uprisings in the world and a new spirit of speaking truth to power? The Guardian - the most ill-named paper in the world - may carry picture after picture from Tahrir Square, but they were willing to sell all the principles that movement stood for straight down the river.

The senior news reporter's attempt to give his paper one last leg-up before retirement left his paper gasping for its liberal breath. When American right-wingers were calling for me to be killed, the Guardian didn't run a single article in my defence. Instead, they got my old friend, the special investigations reporter, to write a dirty little attack on me.

'The Guardian - the most ill-named paper in the world.'

'Strewth', as we used to say. Life was easier when it was just sugar ants running up my legs and biting me to death. At least in those days I had the sun on my side. But in our new kind of business, you soon get over the old guard kicking you when you're down.

We had a month to get the cables in good order, and doing so would be the most exhilarating month of my life. The cables would show the modern world what it really thought of itself, and we worked through the nights in an English country house to meet the deadline.

The snow had begun to fall and it lay evenly over the Norfolk countryside. There was no way to know that the house was to become my prison for the foreseeable future.

You've obviously heard of us, otherwise you wouldn't be here.

We're known for telling the truth even if it's not in our interest.

We're now telling you to beware Apple's walled garden. Don't get locked in.

What you've seen so far may be only the beginning of something far far worse.

Download our Test Drive and at least check out our free Keymaster Solo.

That's the first step to regaining your freedom. See here.

|